FAQs

Who’s proposing to rebuild the Edmonton incinerator?

The North London Waste Authority is in charge. The NLWA arranges waste disposal for Barnet, Camden, Enfield, Hackney, Haringey, Islington and Waltham Forest. It says that part of its primary function is to “promote waste minimisation and recycling.”

Yet recycling rates in North London plateaued over the last decade, and even fell in the year ending 31 March 2019. The NLWA has a longstanding goal of reaching a 50 % recycling and composting rate by 2020, but it’s nowhere near reaching it — it’s stuck below 30%. The incinerator might be a reason for the low recycling rates (see p 9 of this document for more evidence, which applies to the impact of incineration in general and is not specific to the Edmonton plant).

The NLWA is made up of 14 councillors, two from each of the boroughs. Twelve are from the Labour Party and two are from the Conservative Party.

How far along is the project?

Pre-construction phase. Construction on the incineration facility (‘ERF’) is not set to begin until very late in 2022. The construction contract hasn’t yet been tendered. We still have time to change the plan.

There’s no fixed expiry date on the current incinerator. We can take a moment to develop a different plan.

If this project moves forward, what will happen?

We predict that this project would end up as either (a) an environmental nightmare that London can’t escape from or (b) a financial albatross in which the facility has to be shut down, at great cost, because of future climate, recycling and public health laws.

Have such incinerator projects been stopped before?

Dozens of incinerator projects have been stopped in the UK in the past decade.

How can we oppose the incinerator rebuild without a fully-fledged alternative plan in place?

We advocate a stop and think approach. Six of the seven boroughs have declared a climate emergency. If these declarations are to mean anything, the councils will have to develop a better waste treatment plan.

The first step is to acknowledge that an incinerator is not the right way forward. Incineration goes directly against the EU’s circular economy goals, which call for all plastic to be recyclable or compostable by 2030. It is part of the linear economy — ‘make, use, dispose’. Some experts call it ‘skyfill’.

The next step will be to leverage the collective resources and intelligence of the seven boroughs and develop a better plan. A key element of the plan will be sorting. We need to sort rubbish into its constituent parts — metals, plastics, organic materials — to retain their value and keep them in the circular economy.

We’re working on a detailed suggestions document with five to ten concrete and carefully thought-out proposals. Our plan is to reduce the amount of waste in North London — through structural reforms to the system — and send what rubbish remains to a better kind of plant. There are straightforward, proven alternatives.

(Please be patient as we prepare our alternative plan! We have only limited resources, especially compared to the NLWA.)

The NLWA has had many years to plan the incinerator rebuild/expansion and has used a great deal of public money to do so. We propose the NLWA start redirecting its funds towards a plan that meets the environmental and public health needs of the 2 million residents that it works for. We need to come up with a better plan that treats our waste as a resource — a part of the circular economy — rather than a problem.

At the moment the NLWA is instead using our money to sell us its plan. Smooth communications are key to the boondoggle: the NLWA signed a £750,000 contract with a PR firm just for work on this new incinerator project.

Environment & Energy

The NLWA has not released an independent [1] climate impact assessment study, nor made an estimate of the incinerator’s expected total carbon emissions, at least not in public.

However, NLWA has said that the new incinerator would have the capacity to process 700,000 tonnes of rubbish per year. From this figure we can estimate that the carbon emissions will be roughly 700,000 tonnes per year (yes, it’s about one to one).[2] That’s more than the borough of Hackney emits in a year, according to official data.

[1]Last year, the NLWA commissioned a ‘carbon impact screening’ from Ramboll, an engineering and management consultancy that’s in the ‘waste-to-energy’ business. The NLWA used the screening to justify its plan: it cited the screening in a press release declaring that the incinerator project was an important part of tackling the climate emergency. NLWA members also regularly cite figures from the screening when defending the project.

The NLWA did not release the screening until we requested it under an environmental information statute. Only once we obtained it were we able to find the online version buried behind an unfindable slug on an NLWA website.

A quick look at the screening indicates why the NLWA was not eager to subject it to scrutiny.

First, the screening was anything but independent. The NLWA already had a thermal consulting contract with Ramboll — a potential conflict of interest that the NLWA did not declare. Also, Lucy Padfield, a director at Ramboll, is on the Waltham Forest Climate Emergency Commission; meanwhile, a Waltham Forest councillor chairs the NLWA.

Second, the scope of the screening is incredibly narrow: what would be better, incineration or landfill? Ramboll takes no look at the broader rubbish and recycling situation and, again, does not consider any options besides incineration and landfill.

Ramboll does not address the fact that the NLWA, when planning this incinerator rebuild in the early 2010s, projected North London rubbish levels to increase significantly, but they have in fact gone down since that time. More broadly, the screening does not address the fact that rubbish amounts can go down further if councils take stronger action.

The screening is so one-sided that it contains no estimate of the planned incinerator’s total annual carbon emissions, only an incorrect “carbon impact” figure. (We can explain the technical errors upon request.)

It’s also important to note that the NLWA only commissioned the Ramboll study in May 2019, well after the new incinerator plans had been finalized and approved. It’s clear that the NLWA, concerned about public opinion of the project, was merely looking for a post hoc justification of its plan.

[2]How we made this estimate: The current Edmonton incinerator burns more than one tonne of carbon per tonne of waste, according to data from the Environment Agency Pollution Inventory for 2016 (https://data.gov.uk/dataset/cfd94301-a2f2-48a2-9915-e477ca6d8b7e/pollution-inventory). There is no reason to believe this figure would change much when the new facility opens, as carbon emissions are determined mainly by feedstock (that is, what’s in our rubbish bins, not the technology used to burn it).

That the total CO2 emissions will be roughly 700,000 tonnes per year is confirmed by taking a close look at the Ramboll screening. (The figure is implicit in the screening, though not stated outright.)

The incinerator would produce electricity or heat from the rubbish it burns. The NLWA calls the incinerator an ‘energy-from-waste’ or ‘energy recovery’ plant, and even calls the site Edmonton EcoPark.

However, incineration is a very inefficient way to create energy. It captures only a small amount of the calorific value of the materials it burns. This makes it hugely carbon intensive, even more so than burning traditional fossil fuels. Recycling plastic waste is actually a better way to ‘recover’ energy, as the energy saved by not needing to extract fossil fuels and create new plastics is more than that which can be gained from burning it.

There are many alternatives, just in the narrow sense of ‘what type of plant do we want to build?’ These include material recycling facilities, ‘mechanical biological treatment’, steam autoclaving, underground storage of sorted materials, and anaerobic digestion.

The main idea is to have a system that sorts our rubbish and makes the best use of each type of material. A small portion, at least at first, might still end up landfill or incineration, but at nowhere near the scale NLWA currently has planned.

And this isn’t merely a question of what type of plant to build. It’s about the type of waste management system that North London boroughs should have.

The NLWA wants to spend more than £1 billion of our money on a new incinerator when it could invest that money not only on high-tech sorting and recycling facilities, but also in its people — roughly half of the rubbish going to Edmonton could be recycled if people simply threw it in the right bin.[1] If more money were spent on education and awareness raising, much of this ‘rubbish’ could be recycled. In the two-year period ending 31 March 2019, the NLWA spent about £4.3 million developing plans for the new incinerator and less than £2 million on education and waste reduction efforts.[2]

And, it’s crucial to note, we don’t have to rely on education alone. Councils could introduce policies, such as levies or systems in which throwing away rubbish costs money, that dramatically reduce rubbish levels. These are the sort of bold, forward-thinking policies we must have in a climate emergency.

[1] A 2015 report from Barnet — one of seven boroughs that send their rubbish to Edmonton — showed that about 55 to 57 percent of the waste in black rubbish bags (‘residual waste’, in the lingo) is recyclable — and that’s using a very narrow definition of ‘recyclable.’ (If technology improves and/or global commodities markets shift so that it’s not so cheap to make virgin plastics and so on, many more used materials will become valuable and thus widely recyclable.)

[2] Source: NLWA Annual Reports 2017-18 and 2018-19

No, there’s no plan to capture the carbon, and there’s nothing sophisticated about burning all incoming materials en masse. The incinerator will not have any sorting mechanism, such as high-tech scanners that detect the molecular structure of plastics — and sorting materials is the best way to start the process of retaining their value.

In fact, incineration kills innovation. Last year, in testimony before Parliament, the chief scientific advisor to DEFRA said that ‘incineration is not a good direction to go in’ because we should be finding better ways to use the value of materials, rather than turning them into carbon dioxide.

In addition to greenhouse gases, incineration releases nitrogen oxides, sulphur oxides, hydrogen chloride, dioxins, furans, heavy metals, and particulate matter.

The Edmonton incinerator released more than one tonne of PM2.5 in 2018 and more than 2 tonnes of total particulates, according to figures released by the operator. DEFRA says that there is ‘increasing evidence’ that particulate matter leads to respiratory and cardiovascular problems, which can be fatal. Researchers say that ‘no threshold level of PM2.5 is advised as safe for the general population‘.

Most of us wouldn’t consider burning a single piece of plastic, but we allow our councils to run a plastic-fueled bonfire 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. The incinerator literally never stops burning this fossil fuel. The new incinerator, if built, would likely burn more than 150,000 tonnes of plastic per year.[1] Plastic is very light, so imagine how many pieces that is!

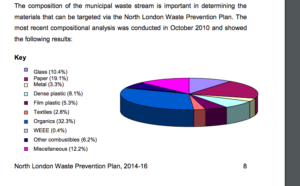

[1] The 150,000 figure is a relatively conservative estimate based on waste composition figures at the existing Edmonton incinerator. The most recent figures that we could find are from 2010.

Please bear in mind that roughly half of the composition of textiles, miscellaneous items, and combustibles that go to the incinerator are made from plastic. This is standard in the industry. It can be seen on page 16 of this report on another incinerator: 50 percent of the makeup of these items is assumed to be non biogenic (plastic).

So the best estimate we have is that about one quarter of the 700,000 tonne capacity at Edmonton would be used to burn some form of plastic.

LondonEnergy, the company that runs the Edmonton incinerator, did not respond to our many requests for more up-to-date info on waste composition.

Finances

The construction alone is expected to cost about £1.2 billion —a figure which has nearly doubled from the original estimate. This figure still doesn’t include operating costs. More importantly, it doesn’t include environmental and public health costs, which, among other problems, lead to financial expenditures.

Yes, it will. The project is funded by council taxes. The NLWA is taking loans from a public borrowing fund, and the seven boroughs will pay back those loans with money from council taxes.[1]

The NLWA has not provided an estimate of how much the project will affect council taxes.

[1] Source: David Cullen, Programme Director for the NLWA incinerator rebuild/expansion. He explained this in response to a question during an Edmonton ward meeting on 25/9/2019. The NLWA has not responded to emails asking for clarification on how the project is being funded (among other questions).

No. The UK has a landfill tax, but no incineration tax. This policy gap is one reason why incineration has become so common in the UK over the last 10 to 15 years.

Incineration is also — somehow — exempted from the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (cap and trade). So while gas-fired power plants pay for the carbon they emit, incinerators do not, even though they emit more carbon per unit of energy created.

The NLWA says it will run for at least 25 years (until 2050). It could run for half a century, like the current plant.

This doesn’t fit with climate goals. There’s an urgent need to reduce emissions to net zero by 2030 — the Labour party recently passed a motion to do so.

If the rebuild goes ahead, the seven boroughs will be paying for the plant — paying back the incinerator loans — for decades, and will have little ability or incentive to fund an alternative waste management program at the same time. This means going green on waste will have to wait another 30 to 50 years.

My Council

Apparently not. The incinerator is in the borough of Enfield, so its emissions are counted as Enfield’s in the official government tally, even though only a small portion of the rubbish comes from that borough.[1]

The other six boroughs should of course be keeping track of the carbon emissions produced by their rubbish, but it’s unclear if they do.

Hackney Council, at least, does not appear to take account of these emissions. In an email exchange with this campaign in late August, a Council representative said that he was not sure whether Hackney’s contributions to the incinerator feedstock were being accounted for in official emissions figures.[2] (Our campaign has since confirmed with BEIS that they are not counted.)

These statistics are being used to declare Hackney London’s greenest borough. A real accounting of Hackney’s emissions — one that included the rubbish Hackney burns at Edmonton — would reveal the borough’s emissions to be 13.2% higher than official statistics showed.[3]

[1] Source: Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) Greenhouse Gas Inventory Team, in an email to Edward Carver on 11/10/2019

[2] The representative was Paul Dobbs, Waste and Environment Manager, Hackney Council. ‘Unfortunately I have no idea about your…question and don’t know who at the council would,’ he wrote in an email to Edward Carver on 30/08/2019.

[3] Here’s the basic math: Hackney’s rubbish makes up about 15.5 percent of that which is burned at Edmonton, according to the most recent NLWA annual report. The incinerator emitted 581,019 tonnes of carbon dioxide in 2016, the last year for which reliable statistics are available. This means that the incineration of Hackney’s rubbish created 90,058 tonnes of carbon emissions in 2016. Hackney’s official emissions total that year, which did not include the incinerator emissions, was 678,100 tonnes. (If we had statistics for a more recent year, the overlooked percentage would be higher than 13.2%, as Hackney’s other emissions have gone down.)

The plan, which has been in the works for many years, is now out of date: the Government’s Resources and Waste Strategy has a 65% recycling target a strong focus on the circular economy. We should avoid institutional inertia and scrap the plan.

Many of the councillors on the NLWA have good environmental records and we respect the work they do. But in response to concerns about this project, they seem more keen to defend their reputations — i.e., their past decisions regarding the incinerator — than to have an open and transparent discussion about the best way to deal with rubbish in North London. They have been very dismissive of our campaign and in most cases declined to engage with us. The following tweet from Councillor Jon Burke, one of Hackney’s two representatives on the NLWA, is indicative of their attitude.